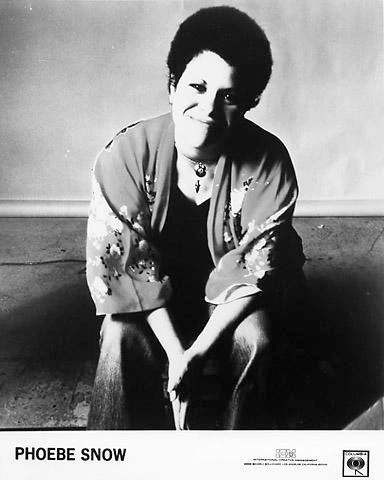

Phoebe Snow: The Light and Shadow of an Unparalleled Voice

Phoebe Snow never fit into the tidy categories the music industry tried to impose on her. Snow was a genre-defying artist in a business that rewards conformity from jazz for pop radio to blues for folk audiences and was too eclectic to be boxed into any one format. She was a singer of staggering ability, with a voice that could vault from a hushed whisper to a full-bodied wail in the span of a phrase. But she was also an artist who faced an industry that often failed to appreciate her depth, a woman who sacrificed mainstream stardom for something more profound, and a musician whose influence outweighed her chart statistics.

The Making of a Singular Talent

Born Phoebe Ann Laub in New York City on July 17, 1950, she grew up in Teaneck, New Jersey, in a home filled with music. Her father was an exterminator who played the violin; her mother was a dance teacher passionate about Broadway. Snow was drawn to folk music early, picking up the guitar and frequenting Greenwich Village clubs. But it wasn’t long before she realized that her voice—a contralto of impossible elasticity—demanded more than the spare, confessional songwriting of the folk revival. She embraced jazz, blues, and soul, shaping an approach that fused technical precision with emotional spontaneity.

Her big break came at the Bitter End, where Denny Cordell, the producer who had worked with Joe Cocker and Procol Harum, discovered her. Cordell signed her to Shelter Records, and in 1974, the Phoebe Snow album debuts. Its standout track, Poetry Man, a wistful, jazz-inflected ballad, became an unexpected Top 5 hit. The song was intimate, floating on Snow’s nimble guitar work and that inimitable voice, its direct and enigmatic lyricism.

The Industry’s Uneasy Relationship with Genius

With Poetry Man, Snow was suddenly a star. The album went platinum, and simultaneously, Phoebe Snow was a Best New Artist nominee at the Grammys. But she was never comfortable with the industry’s expectations. Record executives pushed her toward MOR balladry, eager to mold her into a pop chanteuse. She resisted, leaning into her jazz instincts, which made her an outlier in the corporate machinery of 1970s singer-songwriters.

Her follow-up albums, including Second Childhood (1976) and Never Letting Go (1977), showcased her versatility, shifting between torch songs, soul-inflected grooves, and jazz-based improvisations. Stephen Bishop, who wrote the title track for Never Letting Go, recalled their collaborations as moments of deep mutual respect. Snow also contributed background vocals to his 1980 album Red Cab to Manhattan, gracing Thief in the Night with her unmistakable harmonies.

Yet, despite critical acclaim, the industry’s support wavered. Unlike contemporaries such as Joni Mitchell or Linda Ronstadt, Snow didn’t have a clear commercial niche, and radio programmers struggled to categorize her. As a result, her label’s enthusiasm cooled.

A Life of Devotion and Hard Choices

In 1975, Snow gave birth to her daughter Valerie Rose, who was born with severe brain damage. Many artists balance parenthood with career demands, but Snow’s situation differs. Rather than entrust Valerie’s care to others, she became her full-time caregiver. This decision affected her job; she turned down tours, promotional opportunities, and high-profile collaborations. The industry, rarely kind to women who deviate from the script, essentially moved on.

She continued recording sporadically in the 1980s and 1990s, releasing Something Real (1989) and I Can’t Complain(1998), which reminded her of her extraordinary talent. But by then, she was more of a cult figure than a commercial force, beloved by those who understood her genius but ignored by the mainstream music press.

The Reverence of Peers and Her Lasting Influence

While the industry may have failed to embrace her fully, fellow musicians never stopped singing her praises. Paul Simon, Steely Dan, and Jackson Browne sought her out for collaborations. She worked with Donald Fagen and Michael McDonald, and her background vocals became an uncredited treasure on many era records.

Her ability to bend and shape notes effortlessly and profoundly intentionally influenced a generation of singers. Rachael Price of Lake Street Dive, Norah Jones, and even contemporary jazz-pop vocalists like Lizz Wright owe a debt to Snow’s fearless approach to phrasing and tone.

A Final Bow and an Unfinished Story

In 2010, Snow suffered a brain hemorrhage and never fully recovered. She passed away on April 26, 2011, at the age of 60. In the wake of her passing, tributes poured in—from fans and musicians who had long regarded her as one of the greats.

Stephen Bishop’s recent Instagram post reflects the affection and admiration she continues to inspire. “Phoebe had a heart of gold, an unmatched talent, and remains deeply missed,” he wrote, alongside a photo of Snow with her daughter and husband. “Fans echoed his sentiment, remembering her as a singular voice in American music.” (1)

Why Phoebe Snow Matters

Phoebe Snow was never just a singer; she was an interpreter, a risk-taker, and a musician of staggering depth. Her voice—sometimes playful, sometimes aching—remains one of the most distinctive sounds in modern music. And while she never achieved fame like some of her peers, her impact is undeniable.

For those willing to listen beyond Poetry Man, a treasure trove of artistry is waiting to be rediscovered. Harpo’s Blues is a masterclass in phrasing, Two-Fisted Love is as raw and powerful as anything Janis Joplin ever delivered, and Never Letting Go remains one of the most moving ballads of the 1970s.

Phoebe Snow’s story is one of brilliance and sacrifice, of an artist unwilling to compromise her art or her love for her daughter. The music industry never fully understood this story, but it resonates deeply with those who appreciate true artistry.

And perhaps that is the most incredible legacy of all.

(1) King, J. A. (2022, August 27). Author. Retrieved February 7, 2025, from https://www.dukebasketballreport.com/

After staying up all night to watch game three of the 2013 World Series, my parents and I had a mid-afternoon breakfast. After a summary debate on the interference call against Will Middlebrooks that gave the Cardinals the win, the conversation naturally shifted to music. My dad brought up my recent review of Roy Orbison, waxing lyrical over his golden voice.

What a marvelous phrase: “wax lyrical.” I know it well because my father constantly waxes lyrical. The last album he heard is nearly always the greatest album ever made. Due to his penchant for lyrical waxing, he would be the worst music critic in history, but I do love his enthusiasm.

Anyway, he was talking about The Beatles’ experience on tour with Orbison and how one mentioned that they hated following Roy because he would go out there and just “slay” the audience (it was Ringo, I reminded him). Language-sensitive bitch that I am, I was struck by the use of the word “slay” in the context of enjoying someone’s music. After quietly pondering whether the classic sex-death metaphor could be extended to a music-death metaphor, having already established the music-sex link several times in my reviews, I cleared my head and rejoined the conversation with the first question that came to mind.

“Did you ever hear a singer who slayed you?” I asked my parents, expecting a pause, a long list or a debate.

“Phoebe Snow!” they immediately cried in unison.

I sat there with my mouth agape, having fortunately swallowed the last bite of omelet before agaping. Though their tastes are generally similar, it’s rare to hear my parents in total agreement about anything having to do with music. My father’s lyrical waxing always butts heads with my mother’s pristine precision. Dad will listen to something like Eldorado and say to Maman, “Eldorado was the best thing ELO ever did.” My mother will respond, “Perhaps,” and then remind him how “Boy Blue” repeats the verse pattern over and over to the point of irritation. She might then suggest that On the Third Day could be the better album, and my dad would look at her like she was crazy, largely because he hadn’t listened to On the Third Day that morning, so it couldn’t possibly be ELO’s best album.

Not this time. Total, instantaneous agreement. I let them both wax lyrical about Phoebe for a while, describing the almost orgasmic responses from the crowd when she allowed her voice to rise in a glorious crescendo and claiming that no popular singer’s vibrato was as strong and consistent. At the end of the wax job, they both insisted that I write a review of her début album.

Provided to YouTube by Universal Music Group Poetry Man · Phoebe Snow Phoebe Snow ℗ 1974 Capitol Records, LLC. Released on: 1995-01-01 Producer: Dino Airali Producer: Denny Cordell Producer: Phil Ramone Composer Lyricist: Phoebe Snow