John Adams: Part 5: Unite or Die

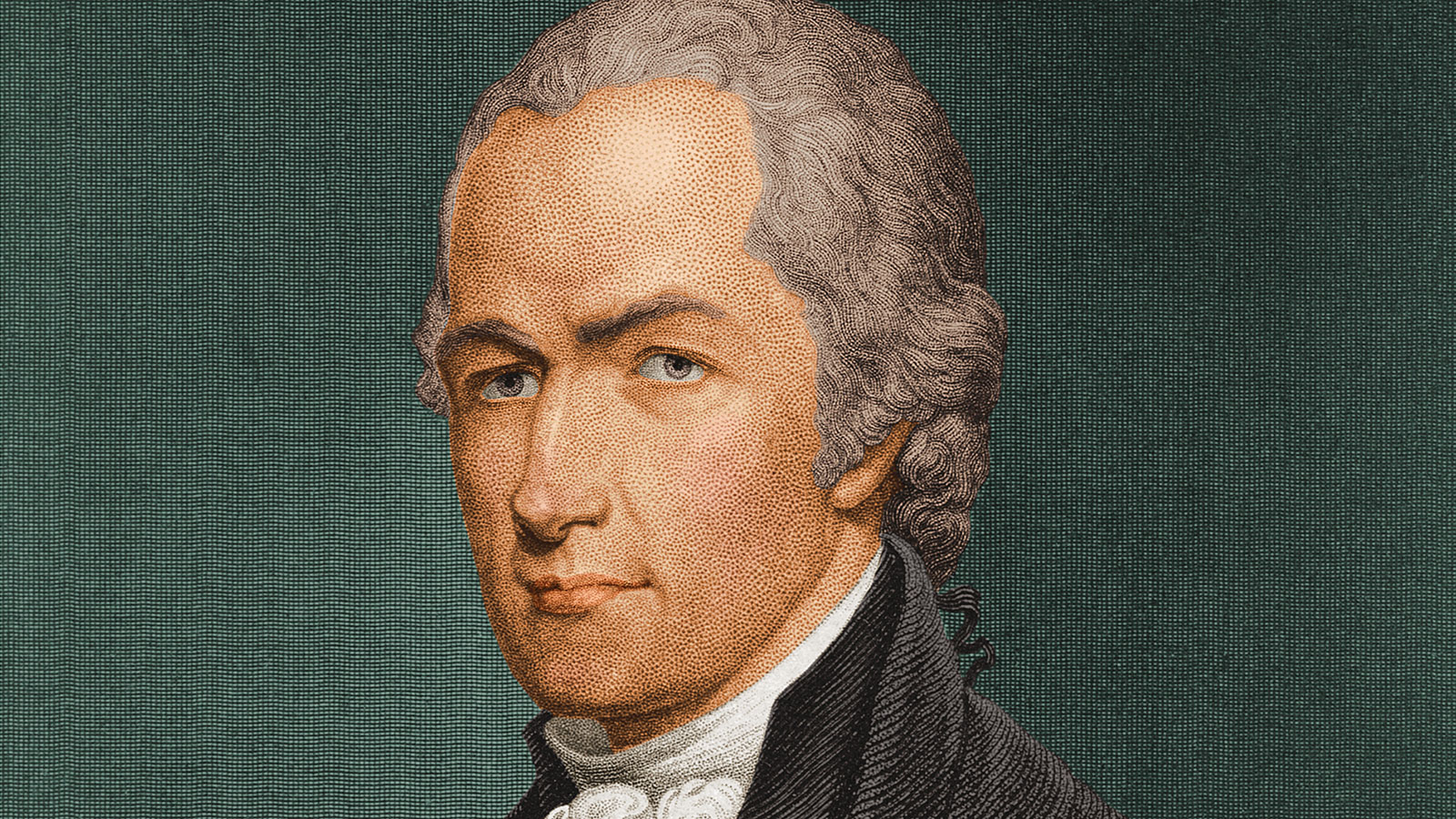

HBO John Adams Alexander Hamilton explains the US Treasury Central government theory to Jefferson.

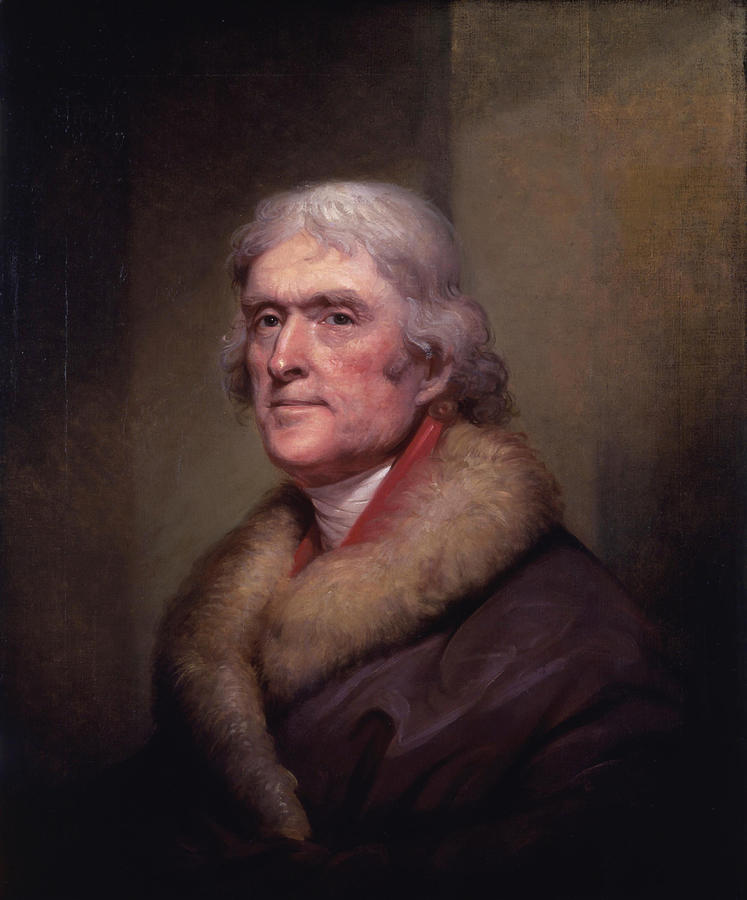

Hamilton vs. Jefferson: The Founding Fathers’ Clash That Shaped America

The Hamilton Broadway musical may give the impression that Alexander Hamilton was universally admired during his time, but historical accounts paint a more complex picture. In reality, Hamilton was a polarizing figure, clashing with other key Founding Fathers, notably John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, over the formation of the United States’ constitutional republic and its future direction. These disagreements went beyond personal animosities and touched on fundamental differences in how they envisioned the nation’s economic and political foundations.

One of the most significant areas of divergence between Hamilton and Jefferson was their view on national debt and the financial future of the United States. Hamilton advocated for the establishment of a National Bank, akin to today’s Federal Reserve, which would allow the U.S. government to borrow money from foreign nations such as Great Britain and the Netherlands. He believed that managing a national debt responsibly could actually be a source of economic strength, binding creditors to the new nation and encouraging economic growth.

In stark contrast, Jefferson was wary of saddling future generations with debt incurred by their predecessors. He feared that leaving behind a legacy of debt would burden children and grandchildren, potentially jeopardizing the nation’s long-term stability. Jefferson’s agrarian vision of America led him to be suspicious of concentrated financial power, particularly in the Northeast, where he believed Hamilton’s policies were creating a wealthy, powerful elite centered in places like Massachusetts. He worried that the national treasury, under Hamilton’s influence, would lead to an unhealthy concentration of power and wealth, which could undermine the republican ideals upon which the nation was founded.

These ideological battles between Hamilton and Jefferson were not merely academic; they had real and lasting impacts on the development of American political and economic systems. Hamilton’s vision ultimately led to the creation of a strong central government with a robust financial system, setting the stage for America’s rise as an economic powerhouse. On the other hand, Jefferson’s emphasis on limited government, individual liberty, and skepticism of financial elites influenced generations of Americans who feared the overreach of centralized power.

The legacies of Hamilton and Jefferson’s debates can still be felt today, as the United States grapples with issues of federal power, economic policy, and the role of government in managing national debt. Understanding these historical debates not only provides insight into the origins of American political thought but also informs the ongoing discourse about the country’s future direction. The clash between Hamilton and Jefferson serves as a powerful reminder that the story of America is one of continuous negotiation between competing visions, each striving to shape the nation according to their ideals.

Hamilton vs. Jefferson: The Founding Visions that Shaped America

“We live, without question, in Hamilton’s America,” says Stephen F. Knott, professor of national security affairs at the United States Naval War College and co-author of Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance That Forged America.

Knott’s observation captures the essence of Alexander Hamilton’s lasting influence on the United States. Hamilton had the foresight to envision America as a formidable economic and military power, surpassing Great Britain and other European nations. As the first Secretary of the Treasury and President George Washington’s closest advisor, Hamilton aimed to unify the nation under a strong federal government. He wanted Americans to think of themselves primarily as citizens of a single nation, rather than as residents of individual states like New York or Virginia.

When Hamilton took on the role of Treasury Secretary, the United States was a patchwork of states with diverse interests, not unlike the differences one might find between someone from South Carolina and another from New Hampshire. Hamilton sought to bridge these divides by creating institutions that would tie citizens more closely to the national government. His establishment of the National Bank and the assumption of state debts from the Revolutionary War were pivotal in creating a unified American identity, setting the foundation for the nation’s financial stability and growth.

Knott asserts that without Hamilton’s contributions, the United States might never have become the economic powerhouse it is today. Hamilton’s vision, which stood in stark contrast to that of Thomas Jefferson, pushed the country toward industrialization and economic expansion. While Jefferson favored an agrarian society with limited government intervention, Hamilton believed in the importance of a robust central government that could support manufacturing, establish a good credit rating, and protect American industries through tariffs. These policies not only stabilized the nation’s finances but also laid the groundwork for America’s emergence as a global economic leader by the late 19th century.

Hamilton’s influence extended beyond his economic policies. He was a key force behind the Federalist Papers, penning 51 of the 85 essays that argued for a strong central government and laid the theoretical blueprint for what he termed an “energetic executive.” His vision of a powerful, enduring federal government was closely followed by Washington, much to the dismay of Jefferson. Knott notes that without Hamilton’s influence, the precedents set during Washington’s presidency would have been markedly different, possibly leaving the young nation more vulnerable to foreign threats and domestic instability.

Hamilton’s idea of a united, “continental” America was instrumental during the country’s most challenging times, including the Civil War. His concept of a strong union was so deeply embedded in the North that Union soldiers were willing to fight and die for it. It’s no surprise that during the Gilded Age, Hamilton was revered as a pivotal figure, admired by presidents like James Garfield and Benjamin Harrison for his vision and leadership.

While Hamilton’s America triumphed in establishing a strong, unified, economically vibrant nation, Thomas Jefferson’s legacy is equally significant. Jefferson championed the separation of church and state, advocating for a government free from religious interference—a principle that became a cornerstone of American democracy. He believed in local control, decentralized government, and an agrarian society that would allow citizens to live independently of centralized economic forces.

Jefferson’s accomplishments, such as orchestrating the Louisiana Purchase, expanded the nation’s territory and paved the way for its transcontinental growth. His commitment to education led to the founding of the University of Virginia, which revolutionized higher education in America. Jefferson’s influence extended to land reform, advocating for the dismantling of primogeniture and entail, ensuring a more equitable distribution of land and the promotion of republican ideals.

Although Jefferson believed in limited federal power, he recognized the necessity of a strong national government in matters of diplomacy and defense. The debate between Jefferson’s and Hamilton’s visions reached a turning point with the election of 1800, often referred to as the “Revolution of 1800.” Jefferson’s victory signaled a triumph for republican ideals and a rejection of the more aristocratic governance model championed by Hamilton’s Federalist Party. This election underscored the enduring tension between centralized authority and states’ rights—a tension that continues to shape American political discourse.

Ultimately, the legacies of both Hamilton and Jefferson have profoundly shaped the United States. Their competing visions for the country laid the foundation for the complex interplay of federal and state powers, economic strategies, and democratic principles that define America today. Understanding their contributions provides valuable insight into the origins of the nation’s political and economic landscape and helps us appreciate the nuanced balance of ideas that continue to guide American governance.

Confident your Republic can withstand four years of Authoritarian rule in these United States? Consider for a moment how our National divide is today compared to 2015. How did our founding fathers source information about the tenure and Fragility of democratically elected Republics? Adams, Jefferson, and Madison all looked to Cicero. Cicero: Defender of the Roman Republic Cicero was a Roman orator, lawyer, statesman, and philosopher. During political corruption and violence, he wrote about what he believed to be the ideal form of government.

HBO’s John Adams – Thomas Jefferson and John Adams’ faith in humanity

John Adams – The Miniseries (Adams meets Col. Washington)

“Whose Revolution?” : John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

One of my favorite scenes from the JA miniseries is when Tom tells John he is resigning. I just love Paul Giamatti’s and Stephen Dillane’s acting in this scene.

Tom: “To the Revolution.”

John: “Whose?”

Show

John Adams: Part 5: Unite or Die

David McCullough on John Adams

librarian of Congress James H. Billington engages noted author and historian David McCullough in a discussion on John Adams.

Speaker Biography: James H. Billington is the 13th Librarian of the United States Congress.

Speaker Biography: David McCullough is an American author, narrator, historian, and lecturer. He is a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award and a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United State’s highest civilian award.

On September 21, 2004, The John Adams Institute hosted an evening with David McCullough. To celebrate the 2004-2005 lecture season, the John Adams Institute paid tribute to the American patriot, John Adams, who provided the institute with both the original inspiration and namesake. 2005 marks the 225th anniversary of his arrival in Amsterdam, and for the inaugural lecture, we welcomed his biographer, David McCullough.

Credited by The New York Review of Books as ‘by far the best biography of Adams ever written,’ John Adams is as engaging a read as it is historically enlightening. In McCullough’s acute portrayal, not only Adams, Jefferson, Franklin, Hamilton, and Washington emerge as fully-formed.

David McCullough is one of the foremost biographers in America. John Adams was a national bestseller and TIME magazine’s best nonfiction book of the year in the year of its publication, 2001.

David McCullough: 2019 National Book Festival

David McCullough discussed “The Pioneers: The Heroic Stories of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West” at the 2019 Library of Congress National Book Festival in Washington, D.C.

– David McCullough has twice received the Pulitzer Prize for “Truman” and “John Adams” and twice received the National Book Award for “The Path Between the Seas” and “Mornings on Horseback.” His other acclaimed books include “The Johnstown Flood,” “The Great Bridge,” “Brave Companions,” “1776,” “The Greater Journey” and “The Wright Brothers.” He receives numerous honors and awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation”s highest civilian award. His new book is “The Pioneers: The Heroic Stories of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West.”

David McCullough Charlie Rose ‘1776’ Interview (2005)

The election of George Washington was weirder than you think

The first U.S. presidential election in 1789 had none of the features Americans associate with elections today: no campaigning for office, no political parties or conventions, and no primary elections. Election Day was in January rather than November. The Electoral College was taken seriously rather than being treated as a formality. This was the only election in which a state was disqualified from participating. And there was only one issue at stake: whether the Constitution itself should be scrapped.

The final results of the election were that George Washington received 69 electoral votes and John Adams 34, making them president and vice president, respectively. John Adams should have received at least 49 votes, but many of the electors who wanted to vote for him voted for other people instead because of a scheme that Alexander Hamilton helped create. So instead of Adams receiving 71% of the electoral vote as he would have, he only received 49%

.0:00 Introduction 0:35 Why 1789? Why not 1776? 2:59 The procedure for electing the president 6:41 How the states chose their electors 8:54 The major election issue 9:58 The New York debacle 12:04 What the anti-federalists wanted 16:46 The plot to prevent Adams from accidentally becoming president 17:31 Electoral College results 20:10 Conclusion

FOOTNOTES

DHFFE = The Documentary History of the First Federal Elections, 4 vols. (Madison: the University of Wisconsin Press, 1976–89)

[1] Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (Chapel Hill: the University of North Carolina Press, 1969), pages 128–132

Jere R. Daniell, Experiment in Republicanism: New Hampshire Politics and the American Revolution, 1741–1794 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1970), page 210

[2] Neal R. Peirce, The People’s President: The Electoral College in American History and the Direct-Vote Alternative (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1968), pages 39–48

Lawrence D. Longley, The Electoral College Primer 2000 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), pages 18–19

[3] New Hampshire: The New Hampshire Election Law, 12 November 1788, DHFFE 1:790

Massachusetts: The Massachusetts Election Resolutions, 20 November 1788, DHFFE 1:510

[4] Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, chapter 13

Jere R. Daniell, Experiment in Republicanism, pages 210–214

Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), pages 15, 35

The image shown here is the mural “The Anti-Ratification Riot in Albany, 1788” created in 1935 by David Cunningham Lithgow, located in Milne Hall at the University at Albany.

[5] Alexander Hamilton to James Madison, 23 November 1788, DHFFE 4:95

William Tilghman to Tench Coxe, 2 January 1789, DHFFE 4:125

Alexander Hamilton to James Wilson, 25 January 1789, DHFFE 4:148

[6] James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, 8 December 1788, DHFFE 4:109

Edward Carrington to James Madison, 19 December 1788, DHFFE 4:115

Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), 31 December 1788, DHFFE 4:122

A Marylander, Maryland Gazette (Baltimore), 2 January 1789, DHFFE 4:126

Marcus Cunliffe, “Elections of 1789 and 1792” in History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–2001, vol. 1, edited by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. (Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2002), page 15

[7] Tench Coxe to Benjamin Rush, 13 January 1789, DHFFE 4:140

Alexander Hamilton to James Wilson, 25 January 1789, DHFFE 4:148

Wallace & Muir to Tench Coxe, 25 January 1789, DHFFE 4:149-150

Tench Coxe to Benjamin Rush, 2 February 1789, DHFFE 4:160

Marcus Cunliffe, “Elections of 1789 and 1792” in History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–2001, vol. 1, pages 13–15

John Ferling, John Adams: A Life (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992), pages 298–299

Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (New York: Penguin, 2004), page 272

[8] William Stephens Smith to Thomas Jefferson, 15 February 1789, DHFFE 4:178

John Trumbull to John Adams, 17 April 1790, DHFFE 4:290

[9] Benjamin Rush to Tench Coxe, 19 January 1789, DHFFE 4:144

Benjamin Rush to Tench Coxe, 5 February 1789, DHFFE 1:401

[William Bradford, Jr., to Elias Boudinot], 7 February 1789, DHFFE 4:168

Federal Gazette (Philadelphia), 9 February 1789, DHFFE 4:172

[10] William Tilghman to Tench Coxe, 25 January 1789, DHFFE 4:149

William Tilghman to Tench Coxe, 9 February 1789, DHFFE 4:172

Benjamin Rush to Tench Coxe, 11 February 1789, DHFFE 4:173

Elbridge Gerry to John Adams, 4 March 1789, DHFFE 4:190

[11] Georgia’s throwaway votes:

James Seagrove to [Samuel Blachley Webb], 2 January 1789, DHFFE 2:438

James Madison to George Washington, 5 March 1789, DHFFE 2:478

[12] John Adams to John Trumbull, 7 April 1790, DHFFE 4:290–291

John Adams to John Trumbull, 25 April 1790, DHFFE 4:291–292

John Adams to Mercy Otis Warren, 20 July 1807, DHFFE 4:292–293

John Ferling, John Adams: A Life, page 299

John Patrick Diggins, John Adams (New York: Times Books, 2003), page 42

Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, pages 272–273

Thomas Jefferson vs Alexander Hamilton (AP US History – APUSH Review)

This is a brief introduction to the conflicts between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton during the Washington Administration that led to the formation of the first two party system in the United States. This lecture is intended for AP US History (APUSH) students but may be helpful to students of government and politics, as well.

From 2001: David McCullough on founding father John Adams

John Adams: The Orator’s Ego

Are you striving to prove the brilliance of the speaker or the truth of that is being argued?

The Burbles

Seven months ago (edited)

In an earlier scene, Willis admitted to Pitt and Thurlow he’d never read Shakespeare – because “I’m a clergyman!” They looked at each other in astonishment and no wonder; for any learned man, that’s a major omission, but for a doctor specializing in ‘afflictions of the mind,’ it is extraordinary because WS’s works included many of the greatest insights and descriptions then available of the problems that beset inner human life.

Extra_050

One year ago

This is significant not only because it’s a real king reading a play about a mad king. Whether or not Lord Thurlow did anything in this scene specifically, his shock as to the propriety of letting George III read King Lear would have been genuine since all play performances were banned during the King’s madness.

A brilliant adaptation of Shakespeare’s King Lear to the remission of King George III’s illness.

For many good reasons, a close companion to the John Adams series is the “Madness of King George” film. This scene, the most poignant and lyrical, of King Lear with the Mad King George in the role of King Lear is a gentle scene of resonant Shakespeare tragedy reverie for King George. One may generously conclude that Shakespeare and the Tragedy of King Lear is the best medicine for what this Royal suffered under. Regardless this scene is ripe with pathos and something close to sublime, credit due to the actors, most especially Nigel Hawthorne as King George, who occupy King Lear’s role with parallel resonance. (1 a)

Widely regarded as one of the greatest stage and screen actors both in his native UK and internationally, the unparalleled Nigel Hawthorne was born in Coventry, England, on 5 April 1929, raised in South Africa, and returned to the UK in the 1950s with his extensive work as a great gentleman of acting following during the decade as well as in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. His portrayal of ‘Sir Humphrey Appleby’ in the BBC comedy Yes Minister (1980) won him international acclaim in the 1980s. In 1992, he was awarded the Laurence Olivier Theatre Award for his sublime interpretation of ‘George III’ in Alan Bennett’s hit stage play, “The Madness of King George III” and he was also nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role in its brilliant film adaptation The Madness of King George (1994), both of them exquisitely directed by Nicholas Hytner. (1 b)

King George III was considered a highly cultured monarch during his long reign. He founded and supported the Royal Academy of the Arts, became the first British monarch to study science, and established a massive royal library. Unfortunately for him, however, most people remember King George III for two things: 1) losing the American colonies and 2) losing his mind.

In a new study published in the journal PLOS ONE, researchers programmed a computer to “read” George’s letters from over his 60-year reign (1760-1820). Their results suggest that the king suffered from “acute mania,” an excitable, hyperactive condition that could resemble the manic phase of what is now known as bipolar disorder.

Using machine learning, the researchers taught the computer to identify 29 written features to differentiate between people with mental disorders and those without. These features included how complex the sentences are, how rich a vocabulary is used, and the frequency and variety of words.

The computer then searched for those features in the king’s letters from different periods in his life. The differences were striking when it compared writings from periods when he appeared mentally sound to those from periods when he seemed unwell.

“King George wrote very differently when unwell, compared to when he was healthy,” Peter Garrard, professor of neurology at St. George’s University of London and a co-author of the new study, said in a statement. “In the manic periods, we could see that he used less-rich vocabulary and fewer adverbs. He repeated words less often, with a lower degree of redundancy or wordiness.”

Garrard and his colleagues also had the computer compare writings from times when other things could have influenced the king’s mental state (different seasons, for example, or during wartime vs. peacetime). In those comparisons, the computer’s analysis found no difference in the king’s language, suggesting the differences it identified were due to mental illness.

Historians and scientists have long struggled to identify the cause of King George’s famous “madness.” In 1969, a study published in Scientific American suggested he had porphyria, an inherited blood disorder that can cause anxiety, restlessness, insomnia, confusion, paranoia, and hallucinations. Researchers noted in 2005 that the king’s doctors might have worsened this condition by treating him with doses of arsenic (i.e., poisoning him).

Widely accepted for many years, the porphyria diagnosis became a long-running play by Alan Bennett, “The Madness of King George.” In 1994, the play was adapted into an Oscar-nominated movie starring Nigel Hawthorne in the title role and Helen Mirren as the king’s long-suffering wife, Queen Charlotte.

(Credit: Public Domain)

But a more recent study, published in the journal History of Psychiatry in 2010, argued against porphyria as the cause of King George’s symptoms. Its authors claimed the earlier research ignored or underrepresented evidence from medical accounts of the king’s condition. They also pointed out that there’s little evidence to indicate George’s urine was significantly discolored (a key sign of porphyria).

In their new linguistic study, Garrard and his co-authors describe the porphyria diagnosis as “thoroughly discredited.” Instead, they write: “In the modern classification of mental illness, acute mania now appears to be the diagnosis that fits best with the available behavioral data.”

The researchers have used similar techniques before when they analyzed how the writings of author Iris Murdoch changed with the onset of her dementia. In the future, they hope to look at how modern patients write during the manic phase of bipolar disorder to create a more solid link to King George and other possible historical cases of the illness. (2)

(1 a) Paul Langan, Cool Media, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

(1 b) Imdb

(2) © 2023 A&E Television Networks, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Who was George III, and was he a bad king?

In this video, made with the support of the Royal Collection Trust, we explore the reign of George III. Was he the aspiring tyrant that comes down to us from the American Declaration of Independence, or has his reign been misunderstood? Find out with Royal Holloway student Sam Angell.

John Adams: A Closer Look (HBO)

How historically accurate is the Musical Hamilton? We know that Miranda made a valiant effort for accuracy yet?

Here is a PDF of the contrast and compare between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamiton (including a Venn Diagram) which clearly diagrams the differences between Jefferson and Hamilton.

Is the BMPCC 4K still worth it in 2021? | STOP ASKING

There seems to be an influx of videos on YouTube asking if “the BMPCC4K is still worth it.” It’s time to stop asking. In this video, we cover why it’s still worth it in 2021 and for the next 5 years. What do you think?

BMPCC4K 2022 | Best budget cinema camera for filmmakers

Should you buy the Black magic pocket cinema camera 4k in 2022? Well, it depends. This is my journey and process on how I came to decide that is was the best camera for me and my budget. I’ve been using the BMPCC4K for over 6 months now so here are my thoughts.

A budding filmmaker like you needs the Blackmagic Pocket 4k VS Hollywood Movie Camera | Red Dragon

BMPCC 4K Review – I spent one year with the Blackmagic Pocket Cinema 4K, am I still in love?

BMPCC 4K Review – I spent one year with the Blackmagic Pocket Cinema 4K, am I still in love? Another BMPCC 4K Review?! I didn’t just buy the Pocket 4K and use it for a week. I used the BMPCC 4K for a full year before producing this in-depth camera review on the Blackmagic Pocket Cinema 4K to provide my fellow filmmakers with the knowledge they need before you purchase the Pocket 4K. Find out why in 2020, I think the BMPCC 4K is the best value cinema camera for filmmakers like you. Learn how I put this entry-level cinema camera to the test when it comes to filmmaking and videography work in the field. In this 1-year review, I also show you some BMPCC4K Footage that I’ve shot, as well as show you some low-light footage from the BMPCC 4K.