The Hissing of Summer Lawns: Joni Mitchell's Jazz-Laden Masterpiece

“Joni Mitchell’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns (1975) is when she abandoned the folk singer-songwriter archetype in favor of something more expansive and cinematic.” (1) The title track embodies this transformation: a hypnotic blend of jazz textures, incisive storytelling, and cool detachment. At its core, the song is a study in tension—between the musicians, the arrangement, and the suburban tableau Mitchell sketches with razor-sharp precision.

Max Bennett’s Bass: The Subterranean Pulse

Beneath the song’s polished exterior slinks Max Bennett’s bass, an uncoiling presence that never demands attention but refuses to be ignored. Bennett, a staple of L.A. Express, doesn’t just hold down the rhythm—prowls through it, his playing elastic yet restrained. Each note carries the weight of unspoken dissatisfaction, a perfect foil to Mitchell’s detached, near-monotone vocal delivery. It’s not just an accompaniment; it’s an undercurrent of unease.

The Arrangement: Jazz as Atmosphere

Mitchell’s increasing fluency in jazz is all over this track, not just in her vocal phrasing but in the very bones of the arrangement. Chuck Findley’s muted trumpet and Bud Shank’s flute don’t solo so much as hover like ghosts over the composition, creating a lush and stifling atmosphere. John Guerin—drummer, co-writer, and Mitchell’s then-partner—lays down a whispering groove, a barely-there pulse that allows every other element to breathe. His synth work adds a shimmer of artificiality, mirroring the song’s themes of surface-level beauty masking an emotional void.

James Taylor’s acoustic guitar is an unexpected but essential texture, a quiet, percussive presence that adds another dimension to the song’s layered restraint. Meanwhile, Victor Feldman’s keyboards inject a jazzy coolness, their precision adding to the track’s eerily composed aesthetic.

Lyrical Themes: Suburban Captivity in Soft Focus

Mitchell’s songwriting has never been about the obvious, and The Hissing of Summer Lawns is no exception. She paints with implication, using fragments of domesticity to sketch a portrait of quiet suffocation.

“He bought her a diamond for her throat / He put her in a ranch house on a hill.“

These aren’t just descriptions; they’re indictments. The language is clinical and distant—just as the protagonist seems to be from her gilded existence. The song’s title perfectly encapsulates its mood: the sound of sprinklers on manicured lawns is artificial, repetitive, and inescapable.

Legacy: The Sound of an Artist Moving Forward

The Hissing of Summer Lawns is a track that doesn’t beg for attention but rewards those who listen closely. Bernie Grundman’s mastery and Henry Lewy’s engineering bring an eerie clarity to the mix, with every instrument occupying its own space with meticulous precision. It’s the sound of Mitchell stepping fully into her powers as an arranger, a sonic architect of moods and meaning.

Initially misunderstood by critics expecting another Blue or Court and Spark, today, the album is one that paved the way for Hejira and her deepening collaborations with jazz luminaries like Jaco Pastorius. The title track, in particular, stands as a masterclass in restraint, a song that suggests more than it says, leaving its tension unresolved, lingering like the hissing of sprinklers at dusk.

(1) Jackson, T. A. (2000). Spooning Good Singing Gum: Meaning, Association, and Interpretation in Rock Music. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8XG9Q3P

The Hissing Of Summer Lawns (2022 Remaster) · Joni Mitchell The Asylum Albums (1972-1975) ℗ 1975, 2022 Rhino Entertainment Company Unknown: Bernie Grundman Flute, Saxophone: Bud Shank Trumpet: Chuck Findley Unknown: Ellis Sorkin Engineer: Henry Lewy Unknown: Henry Lewy Guitar: James Taylor Drums, Synthesizer: John Guerin Unknown: Joni Mitchell Producer: Joni Mitchell Vocals: Joni Mitchell Bass: Max Bennett Keyboards, Percussion: Victor Feldman Writer: John Guerin Writer: Joni Mitchell

The Hissing Of Summer Lawns

Keyboard and percussion – Victor Feldman

Trumpet – Chuck Findley

Sax and Flute – Bud Shank

Guitar – James Taylor

Bass – Max Benett

Arrangement – drums – Moog – John Guerin

When a Brazilian photo-journalist named Wolf Jesco Von Puttkamer took an assignment in the mid-70s to document the lives of the Kreen-Akrore, a reclusive tribe of Amazonian hunters later known as the Panara, there were serious doubts about whether they’d survive the decade. The government had built a highway through their territory in ’73, redoubling their fear of strangers, and the small amount of contact they’d had with the outside world in the past had decimated them with disease. Von Puttkamer found only 130 left alive.

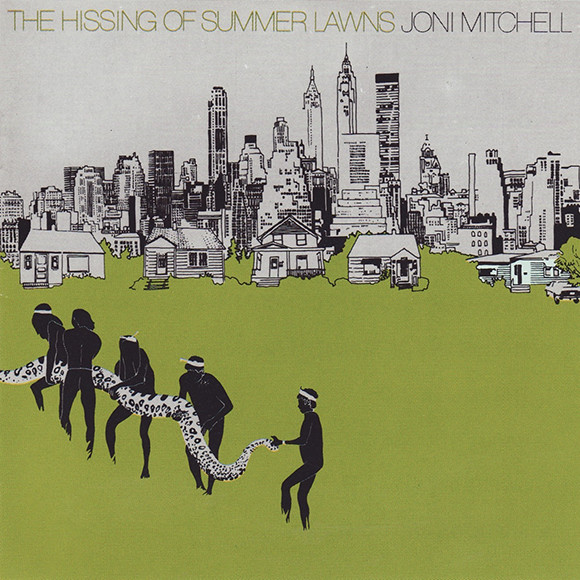

In one of the photos he took, a tiny girl camouflaged in stripes of genipap pulp peers out from a gap in the jungle. In another, the chief of the tribe grimaces as a doctor injects him with penicillin. In another, seven hunters wearing yellow headbands carry an enormous, trussed-up python back to their village from a riverbank. Published in the February 1975 issue of National Geographic, the images were seen by millions of readers, among them Joni Mitchell. While officials in Brasilia had been turning the Kreen-Akrore’s paradise into a parking lot, Mitchell’s live album Miles Of Aisles, with the serene momentum of an adult-oriented superstar going through an invincible phase, had cruised to No two on Billboard, outsold only by Linda Ronstadt’s Heart Like A Wheel. At the beginning of March, Mitchell was chauffeured to the Shrine Auditorium in downtown LA to collect a Grammy for a song on Court And Spark, a pleasant accolade to place alongside its platinum disc. But the python and the boys in the headbands must have stirred something, because she got out her ink, drew the photo from National Geographic and incorporated it into the cover art of her next LP. In doing so, she set in motion a chain of events that shattered the calm, darkened the skies and left her seething about the criticism she never saw coming.

The Hissing Of Summer Lawns is many things. It’s an exclusive peek behind the curtain of palm trees that protects the super-wealthy and the super-bored. It’s a set of 10 musical pieces that are at times melancholy, graceful, fine-woven and inscrutable. It’s a dossier of sophisticated observations on women’s material victories and defeats as they rely on, resent or revolve around their men. Above all, it’s an LP that documents the lives of an endangered species that knows little of worlds beyond its own: the indigenous tribespeople of American suburbia. On the embossed sleeve, Mitchell transposed the giant snake to a fettucine-green landscape that might have been a modern-day urban park. The skyscrapers of a metropolis towered in the distance. Lined up in front of them, occupying the space between the businessmen and the bushmen, a row of bungalows stood like tanks before an army, guarding the city’s perimeter. Mitchell’s motif of the summer lawn was both impressionistic and sociocultural. The incongruous elements of the cover art combined in a visual pun. The hissing sound was made by sprinklers, but a serpent can thrive in a suburban dream-home, coiling itself around a marriage.

Joining some of the dots was “The Jungle Line”, the album’s second song, in which Mitchell traced direct connections from Africa to the jazz clubs of New York, imagining their crammed, noisy cellars as canvasses painted by Henri Rousseau. A primitivist best known for his tropical jungle scenes, Rousseau might well have designed a club décor of “ferns and orchid vines” (as well as putting a “jungle flower” behind the waitress’ ear), but the snake that Mitchell notices in the jazz band’s dressing-room is only a figurative cousin to the real ones in Rousseau’s The Snake Charmer. It’s a “poppy snake” – in other words, the heroin that comes into the city via the trafficking routes that lead back to another humid, vine-thick jungle. To get deeper into the heart of darkness, Mitchell hitches the venue’s wild clientele (“cannibals of shuck and jive”) not to a backdrop of jazz horns, but to pummelling Burundi drums and the electronic growl of a Moog. A totally new event on a Joni Mitchell record, “The Jungle Line” was conceptually provocative and years ahead of its time. The primitive met the avant-garde in the ritual of after-hours safari, and everyone from Paul Simon to Adam Ant was galvanised by the rhythms.

But as the LP cover reminds us, to travel from jungle to city, the primitive must first pass through the suburbs. In isolation and affluence, the suburbanites scatter themselves like plush velvet cushions behind their gadgetry and emotional shields, while Mitchell, with penetrating eye and paintbrush, sees something slithering in their neatly mown gardens. How self-negating are the concessions, she seems to conclude, that yield and are yielded by these unhappy families. Her “third-person lyrical portraits of damaged and unsympathetic characters,” as Elvis Costello once called them, now begin to make their presence felt. They change the tone of the album completely, and with them disappear any realistic prospect of another singer-songwriter confessional. What exactly appears in its place – an air of cold detachment? A sleight-of-hand elegance? An artistry so rarefied that some people don’t react to it while others can’t stop overdosing on it? – has been the subject of debate for four decades.

For example: Edith, picked up last night by a crime boss, awakes in his bed with a song going through her mind. The title eludes her, but her thoughts quickly turn to the man by her side. She won the contest to be his prize for the evening, beating off the competition of older girls, and the criminal empire he runs is not hers to question. She locks eyes with him across the pillow. As the song ends, Mitchell seems to suggest they’re as amoral and desperate as each other: a perfect gangland match. “You know they dare not look away,” she sings, holding one of the album’s longest notes for as long as the two of them can stare without blinking. And that, sure enough, is one way of hearing “Edith And The Kingpin”.

But another way is to listen to the musicians – all of them, or as many as you can – who, far from being emotionally detached, bring sweetness and warmth flooding into the song from all corners. This way of hearing involves smiling with eyes closed as the trumpet on the left is joined by a flute on the right, and once they’ve held their notes for nine seconds, an electric piano (“fresh lipstick glistening”) plays a rippling trill so exquisite that a nearby electric guitar appears to sigh with bliss. Another example: “Don’t Interrupt The Sorrow”, which follows, has often been described as a stream-of-consciousness jazz poem, making it sound like a text of abstruse intellectualism that only someone with a triple First in Classics and Oriental Languages would enjoy. Don’t believe a word of it. Cajoled along by Wilton Felder’s inventively rubbery bassline, “Don’t Interrupt The Sorrow” is a cavalcade of musical delights. Guitarist Larry Carlton’s feather-light glides up and down his fretboard provide so many gorgeous moments that Mitchell stops singing and lets him form them into a solo.

Minutes later, when we meet the highmaintenance Southern belle Scarlett (“Shades Of Scarlett Conquering”), we can count, by all means, the cost of what she loses with her impossible demands while she adheres to the doctrine she absorbed from Gone With The Wind- but we mustn’t forget to swoon to Dale Oehler’s heavenly string arrangement or luxuriate in the dreamy pattern of piano notes that Mitchell reiterates with her left hand. The Rolling Stone reviewer in 1975 who claimed that the album had “no tunes to speak of’ evidently missed the wood for the trees; most of the songs are inundated with instrumental parts of aching loveliness, be it Chuck Findley’s Bacharach-ian trumpet on the title track or his flugelhorn’s haunting three-note refrain on “The Boho Dance”, and their cumulative importance is as absolute as any vocal or lyric. However, as Mitchell would learn, finding not a single tune on The Hissing Of Summer Lawns wasn’t the most scathing accusation the critics in America would level.

There are two more songs about suburban marriages in the album’s second half, and at the end of each one the wife makes a pragmatic decision of sorts. In the title track, an unnamed woman lives as a virtual prisoner on her husband’s hillside ranch (“She patrols that fence of his to a Latin drum”), but chooses to stay because there’s just enough value in their expensive home to compensate for the poverty of her dreary days. As per Mitchell’s album concept, the soothing hiss that the woman can hear from her balcony has worked its mesmeric effect. When it doesn’t, the result comes as a shock. A high-ranking executive on a business trip to New York (“Harry’s House/Centerpiece”) has an erotic daydream about his wife when she was younger (“Shining hair and shining skin/shining as she reeled him in”), before snapping out of his reverie – and we aren’t prepared for it – to reveal in the last few lines that she asked him for a divorce that morning. How old is the woman? Her age isn’t specified. Old enough to be bored out of her mind with her husband, that’s all we need to know. Old enough to be conscious of the moisturizing lotions and the march of time. “All those vain promises on beauty jars, “Mitchell sings in “Sweet Bird”, the next song, just in case a middle-aged divorcee might fancy she’s escaping into a rainbow. “Calendars of our lives, circled with compromise.”

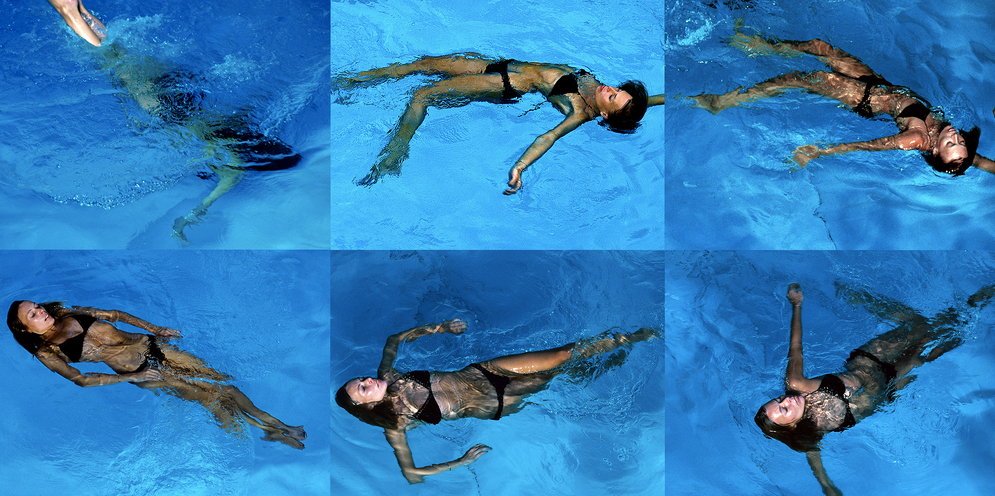

Mitchell, unmarried herself, lived behind wrought-iron gates in her 1920s Bel Air mansion with her boyfriend and drummer, John Guerin. When the gatefold sleeve of Hissing… was opened, there she was, floating on her back in the secluded Eden of her swimming-pool, while 30 lines of album notes, starting somewhere above her right knee, made it clear she was elated with the product inside. “This record is a total work conceived graphically, musically, lyrically and accidentally- as a whole. The performances, were guided by the given compositional structures and the audibly inspired beauty of every player. The whole unfolded like a mystery.” A mystery to be lapped up by hundreds of thousands of armchair sleuths who hung in her every word. But something went wrong. The verdict was not measured out in superlatives this time. Critics dipped their adjectives in scorn (“narcissistic”, “pretentious”, “sometimes so smug that it’s downright irritating”) and her manager had to hide the reviews from her. With its jazz overtones and clear shift away from autobiographical writing, the LP left many fans disappointed. Internet book reviewers condemn a much-hyped novel by saying they “couldn’t relate to any of the characters”. The problem with the album was that some people couldn’t relate to the fact that there were characters at all.

In the 40 years since its release, it’s been place in a much more favorable light. Mitchell was touched when Prince listed it as one of his favorite albums in the 80s. Bjork, Morrissey, and George Michael all sung its praises. Elvis Costello hailed it as “the masterpiece of that time” when he wrote about Mitchell for Vanity Fair in 2004. It’s now celebrated for the very qualities that 70s listeners found hard to tolerate: the icy stillness, the special composure, the delicate balance of colors, the manicured refinement, the considered reportage,

When Mitchell, still furious at the reviews, agreed to a rare interview in ’76, it was with Architectural Digest – a magazine that knew a thing or two about refinement and color balance – whose reporter and photographer came to inspect her Bel Air property that summer. They judged it to be glamorous, but free from contrivance. Showing them the royal-blue dining room and her Eskimo art, Joni explained “Decorated rooms sometimes sacrifice feelings and emotions for the sake of chic. The look is sometimes too polished. I couldn’t live in a house like that.” Too polished. Sacrificing emotions. It was a good job that nobody mentioned lawn sprinklers.

-David Cavanagh, Uncut Magazine 2017