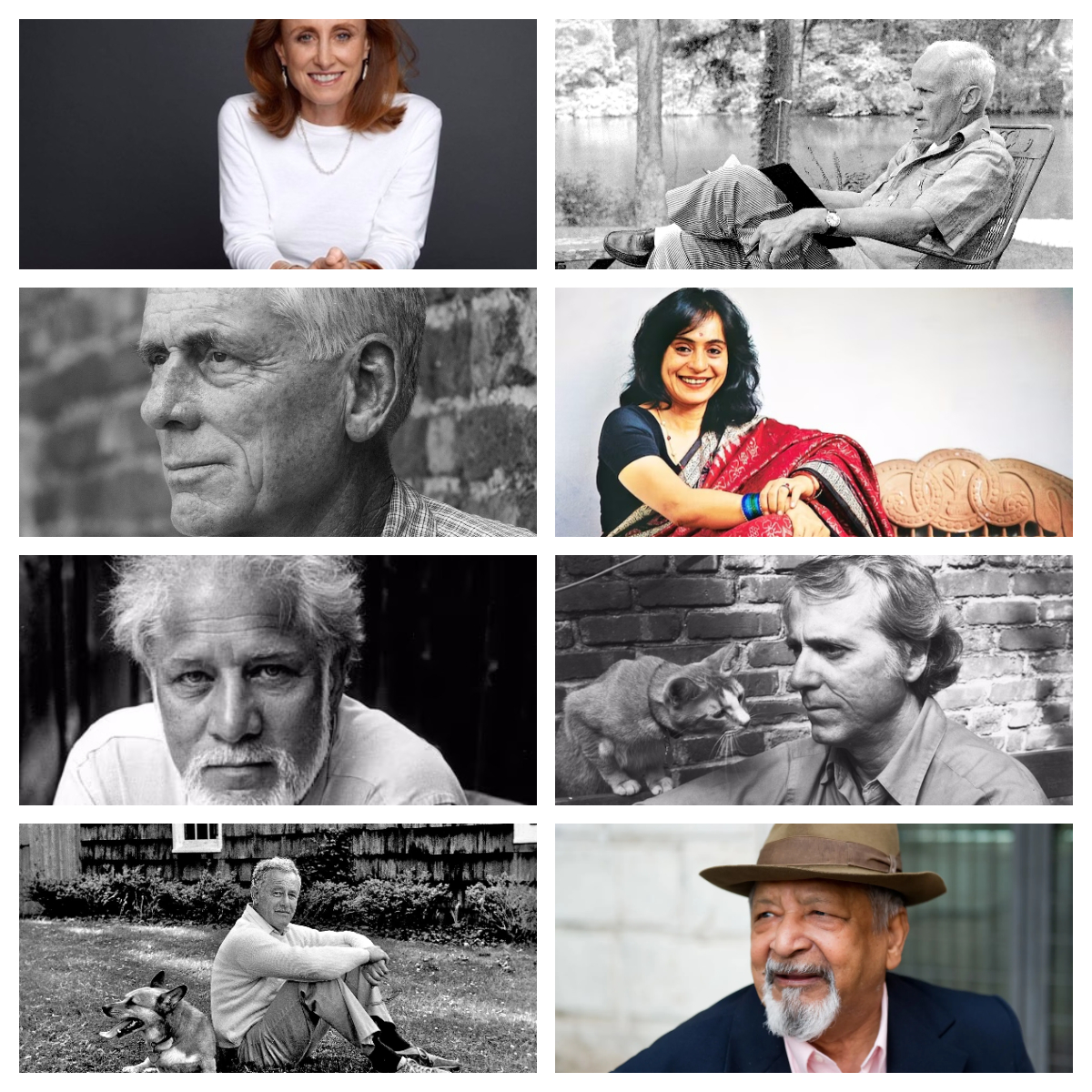

Spalding Gray (June 5, 1941 – January 11, 2004)

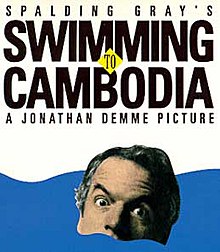

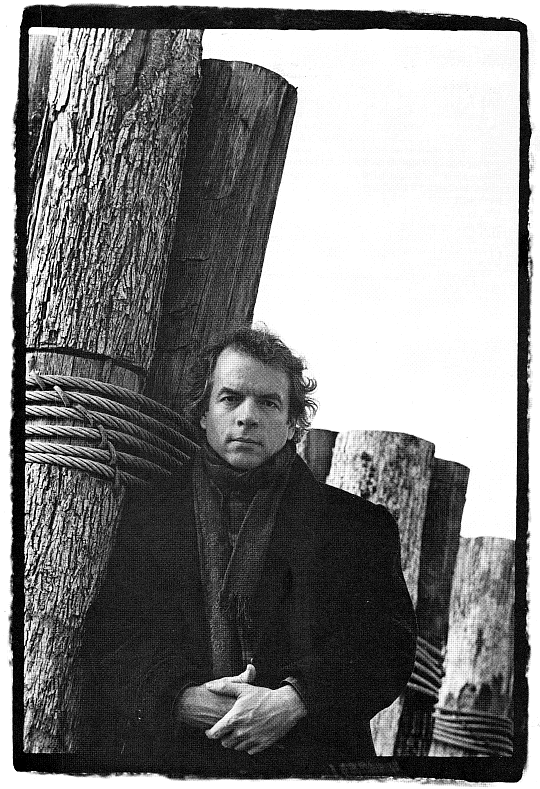

Spalding Gray was a master of hyperbole—a storyteller, monologist, and actor who thrived on live performance. There was an undeniable charisma about him, a magnetic presence that drew audiences in. My first encounter with Spalding was through Swimming to Cambodia. Some might argue that his white, upper-middle-class Rhode Island upbringing created an inherent bias. But to label him as such would be to oversimplify and misunderstand his work. Yes, Spalding was born into privilege, but he deliberately chose a different, less conventional path in his live performances.

Tragically, Spalding’s life ended after years of grappling with suicidal thoughts and dramatizing his struggles. He jumped off a bridge, and his body was found two months later, floating in the East River. Spalding had suffered brain damage from a car accident in Ireland, which left him in excruciating pain and a deep depression. He believed in living fully, convinced this life was his only chance. For him, reincarnation wasn’t a spiritual belief but something he enacted through his monologues, creating a new life moment by moment with his audience.

How did I imagine Spalding Gray’s story would end? I pictured him moderately happy, living in Manhattan with Kathleen Russo, their children, and a big yellow Labrador. Perhaps he would have found new material in the ever-changing landscape of post-pandemic New York City. He might have riffed on the loss of neighborhood character, the overflow of affluence, or his yearning for the ski slopes up north near West Point, like Victor Constant Ski Area. Maybe he’d plan a trip to Bear Mountain and share his thoughts with us. He might have recounted overheard conversations on the subway, mused about disaffected theatergoers, or observed the endless stream of tourists on Canal Street and Fifth Avenue. With each sentence, he could have brought a new incarnation to life right before our eyes.

After watching Steven Soderbergh’s new biographical documentary about the iconic monologist Spalding Gray—entitled And Everything is Going Fine—I invited Gray’s widow Kathleen Russo in to talk about the film. Given the tragic nature of Gray’s suicide almost seven years ago, I expected to meet someone still wrestling with grief, single motherhood, and betrayal.

Instead, Russo—who is also a producer on the film—is an amazingly resilient woman, whose pragmatic candor and optimism shine through every story she tells about her late husband, and about their two sons. Russo was also quite open about Gray’s suicide and the two months of uncertainty that followed. It was a lovely interview, as you’ll soon see.

Tribeca: Do you think Spalding would have approved of this film—of the story you and Steven set out to tell?

Kathleen Russo: Absolutely. Yeah. And in fact, I’ll admit it now that I went to a psychic shortly after we started this project. And he goes, “He’s REALLY excited about the film.” And I hadn’t even mentioned it! So I was like, okay, this must somehow be working. [laughs]

Spalding did this interview with NPR about two months before he died, and he said, “You know, the biggest thing I fear about my death…” and there’s this long pause, “is that I won’t be around to talk about it.” And here he is; you get him for 90 minutes more. He would be so excited!

Spalding Gray – ‘Gray’s Anatomy (1996)

Five years ago

I never really knew much about Mr. Gray, and all I remember is a huge controversy that erupted here in Ireland following the serious car crash that eventually caused Mr. Gray to take his own life. The crash ruined his health and left him in constant severe pain with limited mobility. It was no comfort to Mr. Gray, of course, but his case led to a clampdown on drunk driving in Ireland, which had been virtually ignored before then. This not only undoubtedly saved many lives in the years that followed, but it showed what a crazy country Ireland was and still is in many respects. A talented man, he was very unfortunate in what happened to him.

**Spalding Rockwell Gray was born in Providence, Rhode Island, to Rockwell Gray Sr., the treasurer of Brown & Sharpe, and Margaret Elizabeth “Betty” (née Horton) Gray. He was the second of three sons; his brothers were Rockwell Jr. and Channing. They were raised in their mother’s Christian Science faith. Gray and his brothers grew up in Barrington, Rhode Island, spending summers at their grandmother’s Newport, Rhode Island house. Rockwell became a literature professor at Washington University in St. Louis, and Channing was a journalist in Rhode Island. After graduating from Fryeburg Academy in Fryeburg, Maine, Gray enrolled as a poetry major at Emerson College in Boston, Massachusetts. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1963. In 1965, Gray moved to San Francisco, California, where he became a speaker and teacher of poetry at the Esalen Institute. In 1967, while Gray was vacationing in Mexico City, his mother committed suicide at age 52. She had suffered from depression. After his mother’s death, Gray returned to the East Coast and settled permanently in New York City. Gray’s books Impossible Vacation and Sex and Death to the Age 14 are largely based on his childhood and early adulthood.

Gray killed himself by jumping into New York City harbor on January 11, 2004, aged 62, after struggling with depression and severe injuries following a car accident.

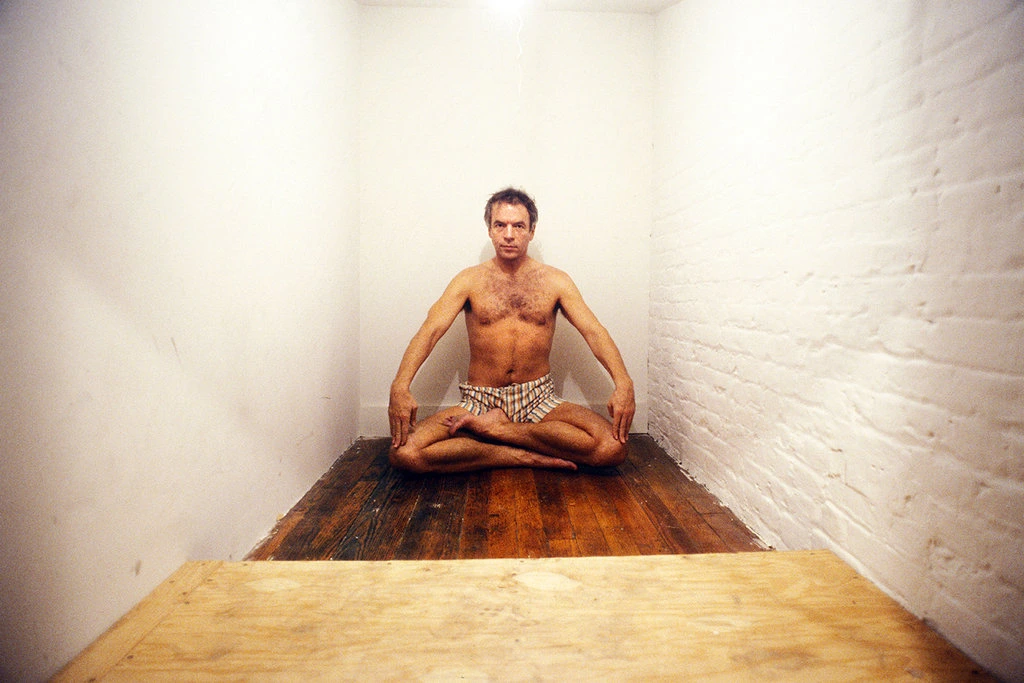

Autoperformance, the work of Spalding Gray, is a

“self-editing” process of storytelling. Based on his

work with Richard Schechner, Elizabeth LeCompte and the

Wooster Group, Gray developed a style of performance that

is uniquely his own. He has developed his performances

into a therapeutic encounters with an audience as he

recounts memories of his life. Some stories are fact,

others are fiction, but they are all universal.

Audiences are enthralled, engrossed, and involved as Gray

tells of growing up in a private school, his sexual

experiences, and his travels across the United States.

He establishes an intimate relationship with the audience

and his tape recorder, which never leaves his table.

Gray has found a way to go directly to the

performance of “self.” He is the performer Spalding Gray

telling stories about the life of the person, Spalding

Gray is the character Spalding Gray. He is himself and

the character at the same time. There is no pretense to

attempt to become someone else. All three—performers,

person and character—are the same. The process

sounds simple enough, as Gray explains it, but the reality

iv

is in the style of the performance. There is an

an important part of wit, intelligence, charm, timing, and

confessional innocence to each performance. Those

qualities have moved Gray from the cultish avant-garde

theatre to Broadway.**

**SPALDING GRAY; THE HUMORIST AND HIS “METHOD.”

by

ADONIA DELL PLACETTE, B.S., M.S.

A DISSERTATION

IN

FINE ARTS

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty

of Texas Tech University in

Partial Fulfillment of

the Requirements for

the Degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

And Everything Going Fine (2010)

And Everything Is Going Fine is a 2010 documentary film directed by Steven Soderbergh about the life of monologist Spalding Gray.

It premièred on January 23, 2010 at the Slamdance Film Festival and was screened at the 2010 SXSW Film Festival and the 2010 Maryland Film Festival.

Soderbergh had earlier directed Gray’s filmed monologue, Gray’s Anatomy (not the TV series, of course).

Soderbergh decided against recording narration and new interviews.

The film instead consists entirely of archival footage, principally numerous excerpts from monologues by and interviews with Gray, spanning some 20 years, as well as home movies of Gray as an infant.

Music for the film was composed by Gray’s son Forrest.

Spalding Gray segment from Swimming to Cambodia (1987)

Best of Dini Petty: Spalding Gray

Understanding Memory: Explaining the Psychology of Memory through Movies

Welcome to Understanding Memory. Someone once said that memory is fascinating because sometimes we forget what we want to remember, and sometimes we remember what we want to forget. Sometimes we remember events that never happened or never happened the way we remember them. I want to show you how memory works, why it sometimes fails, and what we can do to enhance it. Based on my recent book – Memory and Movies: What Films Can Teach Us About Memory (MIT Press, 2015) – I will introduce the scientific study of human memory by focusing on a select group of topics with widespread appeal.

To facilitate your understanding, I will use clips from numerous films to illustrate different aspects of memory – describing what has been learned about memory in a nontechnical way for people with no prior background in psychology. Many of us love watching movies because they offer an unparalleled opportunity for entertainment, even if entertaining films are not always scientifically accurate. Still, I believe we can learn much about memory from popular films if we watch them with an educated eye. Welcome once more.

I look forward to showing you what movies can teach us about memory.

Spalding Gray interview (1997)

“It’s a Slippery Slope.”

It’s a Slippery Slope

Spalding Gray – ‘Gray’s Anatomy’ (1996)

Is the World Real or Just an Illusion?

Is the world real, or is it just an Illusion? This talk addresses a common misconception about the nature of reality: Many classic Advaita texts say that the world is an illusion, but does that mean that it is not real?

Rupert says that the only reason we have problems with this is that, in our culture, we believe that reality means physical things. The question is not whether the world is real or not. It is absolutely real. The war in Ukraine is real. The Caribbean beach we dream of is real. The suffering we feel is real. The question is, what is its reality? What does that question mean? It means not how it appears to be — it means what is it really, despite the way it appears?

Yes, the world is an illusion — that is, it is not what it appears to be. But all illusions have a reality, and that reality is absolutely real. Moreover, there is nothing to an illusion other than its reality. All there is to the world is an infinite being.

As the Sufis say: Wherever you look, there is only the face of God.

This clip is from Rupert’s retreat at the Mercy Center (March 18-25, 2022).